Sŏ Kwangbŏm was one of the earliest Koreans to settle in the United States and was highly influential in nurturing American understanding of Korea and its culture, focusing his attention on educating people in the nation’s capital. As awell-educated Korean from a notable aristocratic family, Sŏ was determined to free Korea (then governed by the 500-year-old Chosŏn dynasty) from its traditional isolationism that had held back development of Western-stylemodernity, while Japan had already embraced it decades earlier.

Sŏ first visited Washington, DC in 1883 as part of an exploratory group of Koreans, members of the Progressive Party, who had been sent by the Korean king on a special mission to the United States soon after the United States and Korea had signed a Treaty of Amity and Commerce (the “Shufeldt Treaty”) in 1882. They were accompanied by the famous American astronomer, Percival Lowell (1855-1916) and a member of the American Navy, Ensign George C. Foulk (1856-1893). One other member of the Korean group was Pyŏn Su 邊燧 (aka Penn Su, 1861-1891), who later became the first Korean graduate of an American college (Maryland Agricultural College, now the University of Maryland). After the group of Koreans had traveled to several major American cities and even met President Chester Arthur in New York City, they split into two smaller groups, and Sŏ returned to Korea via a European route. Clearly, Washington, DC had made a strong impression, and it is not surprising that Sŏ chose to return there later.

Back in Korea, Sŏ and his colleagues in the Progressive Party pursued their goal of modernizing Korea, even taking control of the government in a coup d’état for only three days in late 1884. Sŏ, Pyŏn Su, and a few others then fled Korea, eventually arriving in the United States in June, 1885. Pyŏn Su graduated college in 1891 and went to work for the Department of Agriculture, where he published a survey, “Agriculture in Japan.” Unfortunately, he died in October 1891, struck by a train in what is now College Park, Maryland.

As it happened, another adventurous member of the US Navy, Ensign J. B. Bernadou (1858-1908) had been assigned to Korea between 1883 and 1885. He gathered a large ethnographic collection of Korean artifacts and presented them to the Smithsonian. A few other, smaller collections were also added, and both Sŏ Kwangbŏm and Pyŏn Su made great efforts in describing and cataloging these important early repositories of Korean culture for the benefit of Americans, especially those fortunate enough to be located near Washington, DC.

By 1888, Sŏ Kwangbŏm had settled in Washington and found employment of various sorts, such as in the Bureau of Ethnology (probably working on the Bernadou materials) and various odd jobs, until he obtained a regular, if underpaid, job in the Bureau of Education, located in the historical building that now houses the Smithsonian American Art Museum and the National Portrait Gallery. He developed many friendships in Washington, and newspaper reports indicate that he was highly regarded. In 1892, Sŏ became a naturalized citizen of the United States, while retaining his deep interest in his country of origin.

Being highly educated himself in the Korean manner, Sŏ caught the attention of an important staff member of the Bureau of Education, Anna Tolman Smith (1840-1917), who was an expert on foreign educational systems. He wrote an extended article, “Education in Korea,” published by the Bureau in 1891. No doubt owing to the influence of interests shared with Smith, Sŏ also published some Korean children’s stories in 1893.

Sŏ Kwangbŏm had not been forgotten in his native country, and despite having lived in the United States for nine years and taken American citizenship, he was invited back to Korea (where the political situation was in constant turmoil) in 1894 and appointed to the post of Minister of Justice and later also Minister of Education in the government there. In 1895, however, he was appointed Minister Plenipotentiary to the United States, and on his return to the Korean Legation in DC, the Washington Post (Feb. 16, 1896) reported that he had arrived, and that he “has a host of friends in Washington, who are gratified at his return here under such auspicious circumstances. The diplomatic post in this city has been vacant for some time.” No longer a low-level employee of the Bureau of Education, Sŏ presented his formal diplomatic credentials to President Grover Cleveland the next week.

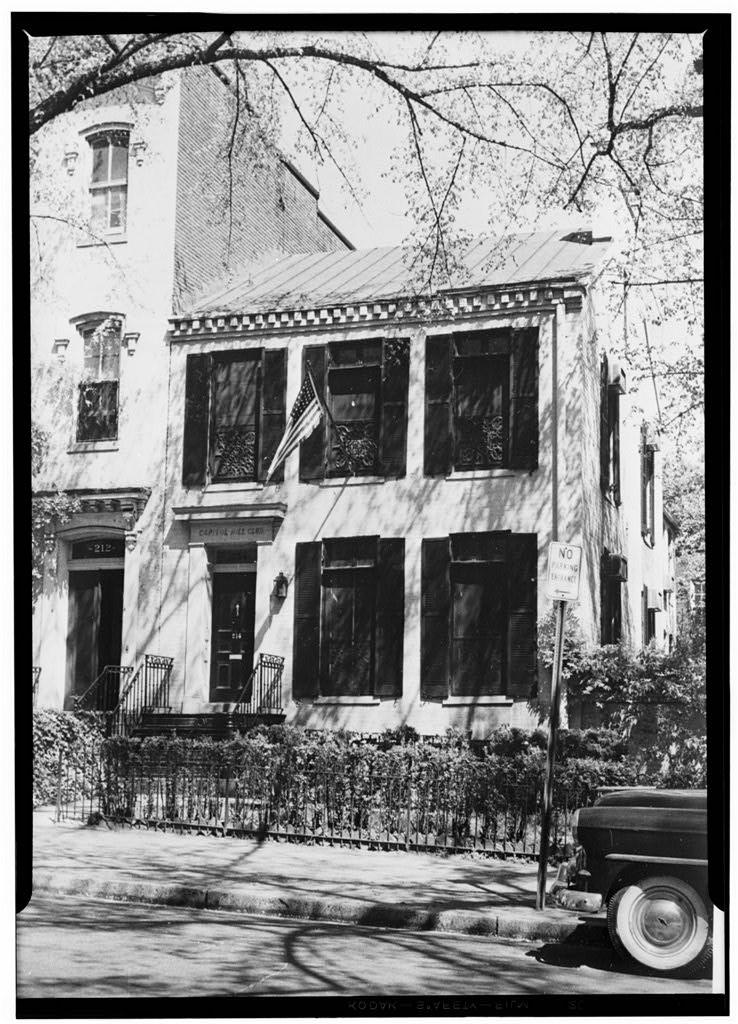

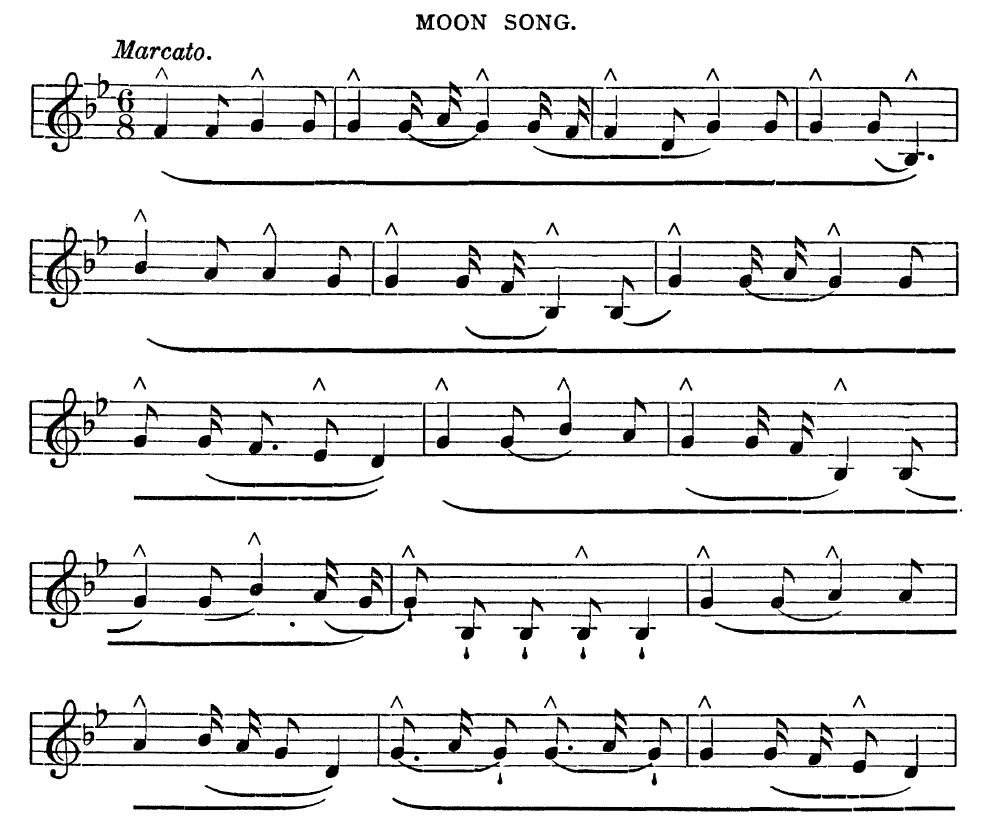

Just a few weeks later, a group of seven Korean students, who had been sent to Japan for study, arrived by ship in Vancouver, penniless and with no English. They were able to contact Sŏ Kwangbŏm, who arranged for them to come to Washington. Sŏ then found them accommodation and educational opportunity at Howard University. A remarkable story followed: Anna Tolman Smith arranged with her close friend Alice Cunningham Fletcher (1838-1923), an anthropologist who possessed a rare Edison wax cylinder recording device, to record a set of cylinders of the singing of two of the students and Sŏ himself. The recording happened at Miss Fletcher’s house near the Capitol building on July 24, 1896, and the resulting six cylinders are the earliest sound recordings of Korean voices, including children’s songs, now still preserved in the Library of Congress. The next year, Anna Tolman Smith published an article in the Journal of American Folklore, “Some Nursery Rhymes of Korea,” largely based on these recordings and, no doubt, what she had learned directly from Sŏ. The recent (re-)discovery of these recordings caused quite a stir in Korean traditional music circles, and the Korean Broadcasting System even produced a documentary on the subject in 2010.

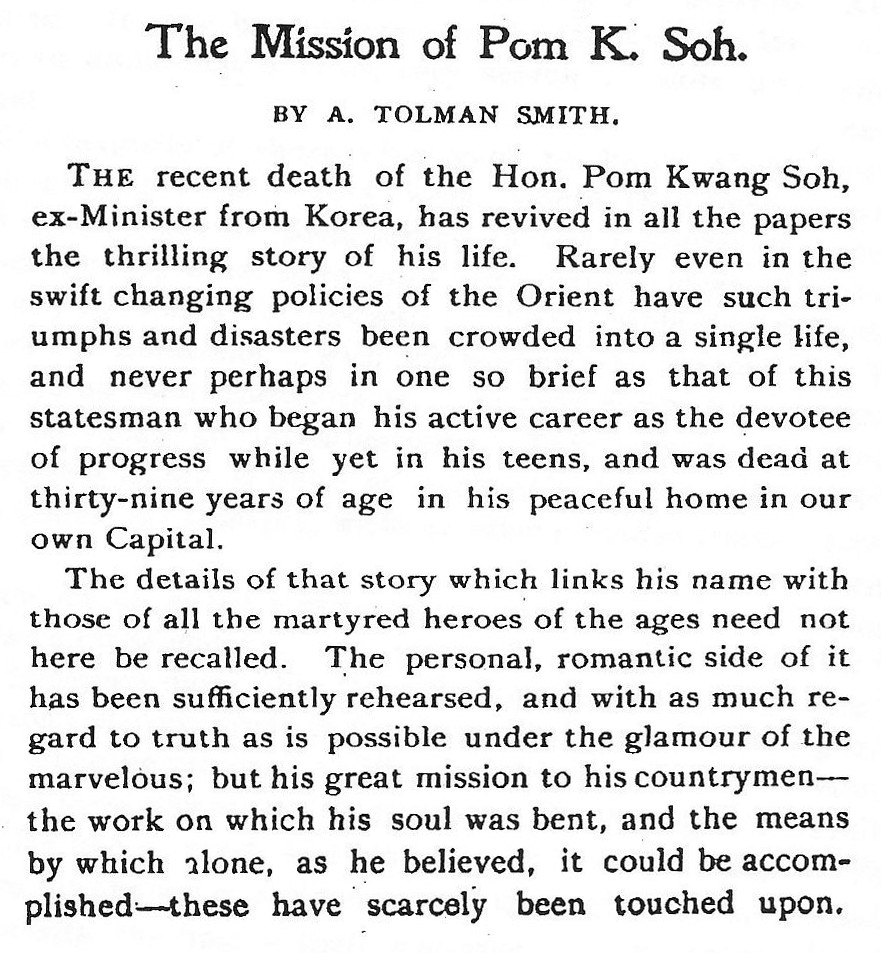

Politics back in Korea continued in great flux, and Sŏ was replaced as Minister in Washington by Yi Pŏmjin 李範晉 (1852-1910), a political foe of Sŏ, in September 1896 only a few months after Sŏ himself had been assigned to that position. Sŏ remained in his adopted country, of which he was a naturalized citizen, and never returned again to Korea, where he would have been in considerable danger. He justified this decision on grounds of ill health (he had chronic tuberculosis), though he managed to travel to England for Queen Victoria’s Diamond Jubilee in June 1897 as one of only a few representatives from Korea. A little more than a month after his return to Washington, Sŏ took a vigorous bicycle ride that aggravated his condition, and he died on Friday the 13th of August, 1897, having lived a remarkably varied, difficult, and influential thirty-eight-year life.

Sŏ Kwangbŏm’s passing was noted by many American newspapers, and Anna Tolman Smith, Sŏ’s steadfast friend and confidant for many years, wrote a heartfelt tribute to him in October 1897 for The Independent, “The Mission of Pom K. Soh,” recalling many details of Sŏ’s life and achievements, especially contributions made during his time in Washington, DC.

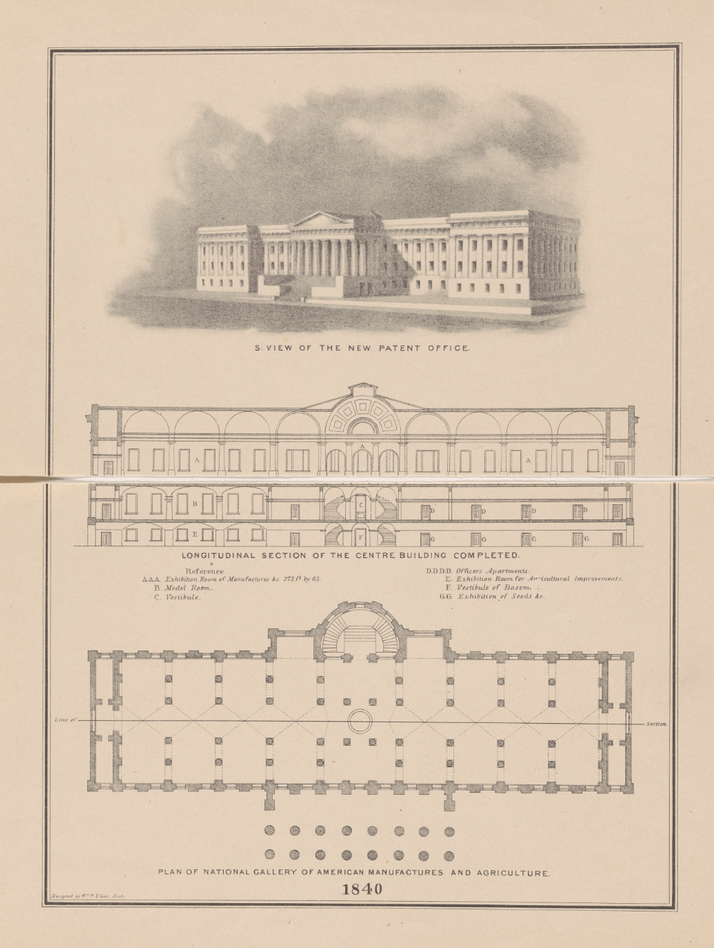

Old Patent Office Plan

The Smithsonian American Art Museum, where the Sightlines exhibition is presented, is in the Old Patent Office Building. From 1852-1917, this building housed the Department of the Interior, which included the Bureau of Education, where for a time, Sŏ Kwangbŏm found work as a clerk, translator, and interpreter.